Pinpoint Ancestry

Bringing your family's past to life

Blog

Poor relief was awarded by Scottish parishes, through ‘kirk sessions’, to people who were unable to support themselves. Recipients included orphans, the old, the sick and those deemed to be insane.

Kirk sessions were church courts. As well as enforcing moral discipline within the parish, they also distributed funds to the weak and needy poor members of the community. These funds were raised from a variety of different sources – church collections, fines imposed by the kirk session for moral crimes such as fornication, fees for carrying out services such as baptisms, marriages and burials, and donations from ‘heritors’ (local landowners).

Following the Poor Law Amendment (Scotland) Act of 1845 boards were set up in each and every parish to administer poor relief. A Poor Law Officer collected information to put before the parochial board. Often there was a debate as to which parish was responsible for providing for impoverished individuals. There were no ‘workhouses’ in Scotland, only ‘poorhouses’.

The good news for family historians is that the poor law officers kept meticulous records – not just of those who were successful in obtaining poor relief, but also those rejected. Details include date of application, name, address, marital status, occupation, disability or reason for application, and the names and ages of spouse and all children. They also list all past addresses.

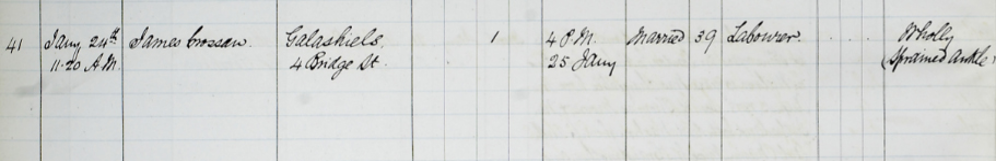

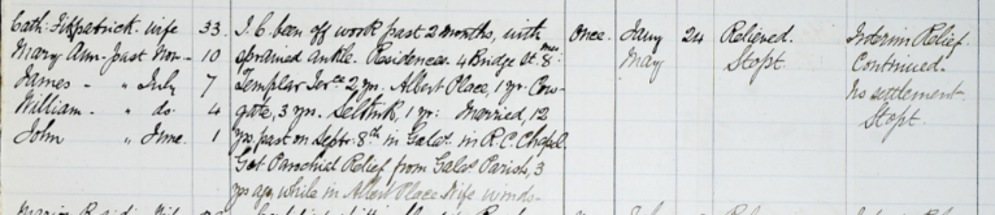

The example below is for James Crossan who was wholly incapacitated by a sprained ankle in 1884. His wife and children are all named and their ages are shown. This allows one to determine what was occurring within a family between census years when other information may be unobtainable. As such, poor law records are a great resource for family historians.

Poor law records can be obtained from local archives such as the Hawick Heritage Hub at Kirkstile, Hawick.

December is traditionally a time when families get together, exchange gifts and cards and catch up on the events of the year. For many of us we welcome new people into our family but sadly each year more and more of our older relatives pass away.

We decorate our trees with family favourite baubles and ornaments – some of which are in a dilapidated state – but we still use them because Christmas would not be the same without those reminders of the past. In our home there are several items that make Christmas special. We still use a nativity set that belonged to my grandmother. The donkey only has three legs now and the ox is missing his horns but they are still placed with affection on the mantelpiece. A Blue Peter Santa Claus made out of a toilet roll, felt and a white pompom sits with pride on the tree despite my children’s best efforts to consign him to the bin – to be fair he’s not looking great but then he is nearly 50 years old!

Christmas is often a time of reminiscing with a glass of sherry and a mince pie – a time of stories about childhood memories from the past. Make time this Christmas to write down those memories so they are not forgotten by future generations. In an ever changing world where it’s easier to send a text or an email than to write a letter, cherish the memories of our older generation without whom none of us would be here today. Perhaps use today’s technology to record their memories. From experience one of the things I miss most about close family members who are no longer with us is the sound of their voices – photographs are wonderful and although they fade with time they remain with families long after people die. But the sound of their voices is gone forever unless you record them.

However your family celebrate Christmas enjoy being together.

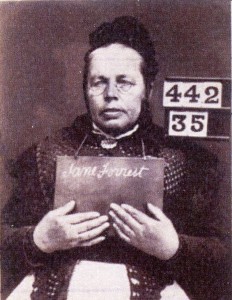

Image courtesy of National Records of Scotland, Crown Copyright NRS HH/21/48/2/44

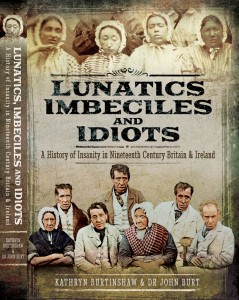

I was interested to attend this year’s special exhibition at the National Records of Scotland set to coincide with the Edinburgh International Festival entitled ‘Prisoners or Patients?: Criminal Insanity in Victorian Scotland’ as it is a topic we at Pinpoint Ancestry have published two books about: Lunatics, Imbeciles and Idiots (2017) and Madness, Murder and Mayhem (2018).

Running from 1 to 31 August 2019 in the Matheson Dome of General Register House at the east end of Princes Street, it is a small but fascinating exhibition and very much reveals how archival records can be used to illuminate the stories of a select number of prisoner-patients who were admitted to the Criminal Lunatic Department of Perth Prison (equivalent to England’s Broadmoor Hospital).

The discipline of psychiatry was in its infancy at this time. Mental health was poorly understood. There is debate as to whether the inmates were treated as prisoners rather than patients. Through the case histories of eight patients, the exhibition examines each individual story, and evaluates how their mental illness touched their own lives and the lives of their families. In each case there are archival documents including legal documents (precognitions and court records), medical records, and prison records which help illustrate their stories.

At Pinpoint Ancestry we have been particularly interested in this aspect of the history of mental health. We have looked at the development of asylums in nineteenth century Britain and the greater understanding of the treatment of mental health disorders. Originally called ‘mad doctors’, they were renamed ‘alienists’ before finally the modern term ‘psychiatrist’ became used.

As part of the special exhibition, on 30 August 2019 we are privileged to be giving a talk at New Register House in Edinburgh entitled ‘Researching Criminal Lunatics: exploring archives’. Admission is free but attendees should book prior to the event on eventbrite.

Dr John Burt

In the First World War over one million British and Empire soldiers, sailors and airmen died. Men would fight and die in their anonymous thousands in the mud of Flanders, the Somme and elsewhere throughout the many fields of conflict. Many of their bodies were never identified or even recovered. ‘Present and correct’ at the start of battle, they were ominously absent from the final muster – and were therefore ‘missing-in-action’. Dog-tags (identity tags), regimental badges and other effects helped to identify some of the bodies who would be recorded as killed-in action (K-i-A). Early simple dog-tags were worn round the necks of soldiers but a new reformed double dog-tag system was instituted by Fabian Ware, a politician and veteran of the Second Boer War, and the founder of the Imperial War Graves Commission (later to become the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CGWC)). Every soldier now wore two dog tags made of pressed fibre – one red fireproof and the other a green waterproof one.

The tags were strung in a particular way – the red tag was easily cut off but the green tag would be left with the body. When the red tag was sent to the adjutant of the regiment it confirmed a killed-in-action death and the next-of-kin would be informed.

Many recorded as ‘missing-in-action’ were never be found. They might have been wounded, captured or a few shell-shocked individuals may have even deserted in terror or suffering from shell-shock (risking being ‘shot at dawn’ by their fellow colleagues for cowardice). However, many were blown to bits, or their bodies decomposed and perished in the rat-infested trenches. They became unidentifiable and bore no resemblance to the smart young men who had gone to war. After a period of time the ‘missing-in-action’ became ‘missing presumed dead’. The names of the missing were known to the authorities but the huge list of names could never be matched to the thousands of unidentified corpses of these victims of war. Throughout the war graveyards of France and Flanders, Turkey, Palestine, Iraq, and elsewhere are thousands of CWGC headstones labelled simply ‘a soldier of the Great War’ without a name.

The Ypres Menin Gate Memorial in Belgium records the names of over 54 thousand soldiers who died before 16 August 1917 and have no known grave. The recently restored Thiepval Memorial in France commemorates more than 72 thousand men of British and South African forces who died in the Somme before March 1918 who have no known grave. The Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing’ records over 33 thousand UK forces and over 1,150 New Zealanders, including three Victoria Cross winners, who fell in either the Battle of Broodseinde or the First battle of Passendaele in October 1917 “whose graves are only known unto God”.

However, some of the missing have been found in recent years thanks to DNA technology. In 2009 the bodies of 250 Australian and British soldiers, buried by the Germans in 1916, were exhumed from the military cemetery at Fromelles in the north of France. Of these, 159 Australian soldiers have so far been identified, enabling the CWGC to erect a new headstone for each of them bearing their name, and bringing closure to their families.

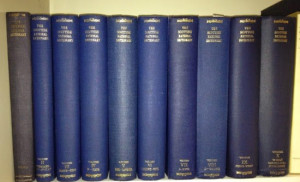

The Scottish National Dictionary was published in ten volumes between 1931 and 1976. The compilers sought out many individuals from all over Scotland who were experts in their local dialect and had a profound knowledge of local history, and could explain Scots words as they appeared in print from 1700 until 1976. The mission of this elite group of individuals was to record, share and promote these words within the context that they were originally written.

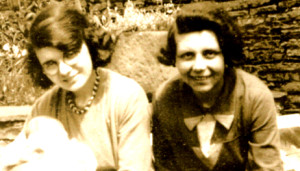

My great-aunt, Jeanie Craik Rodger, a primary school teacher in Forfar, was one of the first expert compilers recruited. She was born in 1905 in Forfar and had a very strong Angus accent. Her family had lived there from time immemorial. She collected the vocabulary, accents and stories of her charges, and stories from local folklore.

Jeanie is shown on the right with her younger sister, Agnes Mary Rodger, who died in 1937 of pulmonary tuberculosis, just 23 years old.

One of her most memorable works was Lang Strang – a book of rhymes and children’s games published in 1948 based on local tales from Forfar – one of the greatest hits was ‘a bedtime story’ where trousers are ‘stuntifiers’ and the cat is ‘Old Killiecraffus’. Jeanie then went on to write a regular column in Forfar vernacular for the national Scots Magazine under the pen-name of ‘Mary-Ann’.

When compiling her entries for the Dictionary she came across a number of words with a specific medical terminology, such as ‘bairn-bed’ for a womb. Some were local to Forfar, but others came from many other parts of Scotland.

As a medical historian I have always had an interest in these ancient terms – some are quite amusing in their frank descriptions. Males had cods, courage-bags, culls, bollocks or knackers, pintles, whangs and wallies! And females had bairn-beds, fud, crappins, craig of the creel, egg-bags, wheeries and problems with their breists or briskets.

Other worrying names are ‘by anesel’ meaning completely mad, and ‘curly wingles’ when apparently you think your guts are doing somersaults. At least you would know your ‘hurdies’ meant your bum.

I am proposing to develop an inventory of Scottish medical terms as part of a Pinpoint Ancestry development to appear on our website soon. All out-kneed people with reeking oxters, peerie-winkled, hertie, driddly and kittle or lap-biggit people are apologised to.

I have been attending WDYTYA Live for many years, but this year was the first time that I’ve given a talk. I’ve spent the last twelve months co-writing a book entitled ‘Lunatics, Imbeciles and Idiots – A History of Nineteenth Century Insanity in Britain and Ireland’ which has just been published by Pen & Sword History. My co-author, John Burt and I were able to give a companion lecture at WDYTYA Live to raise awareness of the valuable records available when researching ancestors in nineteenth century lunatic asylums.

As new authors, we believe we have written a worthwhile book but,of course until we start to see the reviews it has been difficult to determine how much it will be enjoyed by the reader. So, it was very gratifying to be able to see people buying it and providing us with positive feedback.

Without doubt our talk and the book launch was the highlight of the three day event for me. However, getting together with old friends, meeting new ones and assisting on a couple of stands as well as spending time as an ‘expert’ on the Welsh desk was equally gratifying.

Genealogy can be a fairly isolating career in some respects – I seem to spend my day researching the dead which is fascinating but, it’s good to be able to get away from the desk and meet like-minded living people. WDYTYA Live is the perfect annual event. This year  was certainly no exception with a wide range of excellent talks on offer and many genealogy exhibitors and professionals to consult. The Register of Qualified Genealogists (RQG) attended for the first time and provided not only a list of their members but also mini-talks on a range of fascinating topics. These will be made available on their website and are definitely worth watching. The RQG also used WDYTYA Live to launch their new Journal with an interesting first edition about the London Silversmith family, Mewburn by Ian G. Macdonald of the University of Strathclyde.

was certainly no exception with a wide range of excellent talks on offer and many genealogy exhibitors and professionals to consult. The Register of Qualified Genealogists (RQG) attended for the first time and provided not only a list of their members but also mini-talks on a range of fascinating topics. These will be made available on their website and are definitely worth watching. The RQG also used WDYTYA Live to launch their new Journal with an interesting first edition about the London Silversmith family, Mewburn by Ian G. Macdonald of the University of Strathclyde.

As always, the event was both brilliant and extremely tiring at the same time – thanks to my Smart Bracelet I was able to work out just how far I walked each day and averaged about 10km! So despite the fantastic food we ate I still managed to lose a few pounds which has to be a bonus.

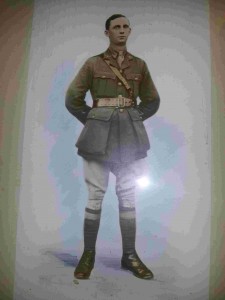

The First World War has always fascinated me – not only because of the tragic loss of human life – but also because my paternal grandfather enlisted in October 1914 and managed to survive the entirety of the conflict.

A missing family member often provides the catalyst for fascination and a desire to find out more about them. And this was certainly the case for me as my grandfather John Capper died six years before I was born. I had photographs to look at, his war medals to cherish and his grave to visit – what I didn’t have was his first hand account of his life.

Why did the youngest son of a farmer from North Wales feel the need to enlist at the start of the conflict? Conscription wasn’t enforced until 1916, so what was his incentive? His grandfather had visited France in the 1860s to deal with the estate of his elder sister – the family still talks about this trip. Did my grandfather want to visit France for this reason? Was he compelled to do his duty to King and country and fight for freedom? Or did he merely wish to go on what he thought would be an adventure that would be over by Christmas? No one could answer that question apart from him and unfortunately it was too late to ask.

I obtained his attestation papers from the National Archives in London – I was lucky, although he had enlisted as a Private with the Cheshire Yeomanry, he was promoted in the field and became a 2nd Lieutenant in the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment. As a result his documents were available for research. The majority of attestation papers were destroyed in the Second War and are known as the ‘Burnt Collection’. Very few remain, but there is a substantial collection for Officers.

So I have been able to read the official version of his war service which has been a bonus, but of course it doesn’t contain his own testimony of his experiences during that time. I am by no means unique in this respect, many people researching their families will be in the same situation. At least I have been able to obtain records about my grandfather, and war diaries that will help me construct in my own mind what his life was like on the battlefields of France. There are also living family members who remember him well but these are becoming fewer with every year that passes.

John Capper 1917

I have researched many families in the course of my work and always pause when I see a generation of sons born in the 1880s and 1890s – knowing that inevitably some of them will have enlisted as my grandfather did. And so, if I discover that they were involved in the conflict I always note it. These men deserve to be remembered even if they didn’t marry and leave children who would one day wonder what they were like.

After several years’ research and countless hours of scribbling I’ve just taken delivery of an advance copy of a book I’ve been writing with friend and colleague John Burt. Coincidentally, the book arrived on Epilepsy Awareness Day.

Lunatics, Imbeciles and Idiots began following our M.Sc. dissertations in Genealogy at the University of Strathclyde and snowballed as a result of the rich sources and fascinating social history that emerged as we researched nineteenth century asylums. We quickly realised that we were researching a very special subject – a taboo topic and one that most families endeavoured to forget if there was any hint of insanity in their family.

Thousands of men women and children were admitted as pauper patients to asylums in Britain – quickly to become a forgotten group of people shut away from the gaze of society and shunned as individuals to be feared. In nineteenth century Britain, mental disorders were little understood and ‘mad-doctors’ or ‘alienists’ as they were called endeavoured to determine the cause of their ‘insanity’ in an attempt to cure or curtail it. Conditions such as epilepsy and post-natal depression which today are cured or managed by modern medicine invariably led at that time to a stay in an asylum.

The nineteenth century saw progress in the medical understanding of epilepsy but the condition was considered incurable. A diagnosis of epilepsy, as well as having a physical and biological impact on the body and brain, also affects the economic, psychological and social aspects of an individual’s life. This impact would have been all the greater during the nineteenth century when medication was limited and the prospects for individuals with uncontrolled seizures were bleak. In 1857, Sir Charles Locock (1799–1875) discovered the anti-convulsant and sedative qualities of potassium bromide and it was regularly used to treat epileptic seizures and nervous disorders until the discovery of phenobarbital in 1912.

Despite early advances in the understanding of epilepsy, the prognosis for patients remained unfavourable and many became long term patients and died in asylums. Epileptic patients were admitted occasionally hoping for a cure but generally because they could no longer be cared for within the home or workhouse. There is evidence from asylum case notes that an asylum was a better option than the workhouse, particularly if the asylum had purpose built provision for those suffering from seizures.

Despite an improved understanding of epilepsy in the nineteenth century, reading asylum accounts of epileptic patients is particularly harrowing. When sisters, Esther and Violet Gosling arrived at Parkside asylum in 1894 they were having frequent seizures and were unable to take care of themselves. Esther expressed a wish to enter the asylum because she wanted to be cured – which wasn’t likely, but, it must have provided her with hope. Esther and Violet were relieved from Parkside back to their family home after a six month stay during which time they received no treatment or cure. Both sisters died within two years from seizures.

Another pair of siblings admitted to the asylum were Mary Jane and John Robert Percival. Mary Jane was only 10 when she arrived at Parkside in 1890 diagnosed with both Imbecility and Epilepsy. She had previously been resident at Altrincham Workhouse but her seizures (which were attributed to fright) led to a transfer to the county asylum. Her younger brother John Robert was only 7 when he was also admitted to the same asylum in 1898 suffering from the same symptoms. It is unlikely that the two met – segregated by the asylum system on opposite sides of the building. Both died in Parkside from pulmonary tuberculosis in their early 20s.

Researching and writing ‘Lunatics, Imbeciles and Idiots’ has been an emotional journey but one we’re glad we embarked upon. Research into epilepsy remains ongoing, but today the prognosis for those who have the condition is much better. Improved medication, understanding and support is now available and epileptics are no longer shunned from society or locked away because of their seizures. The Epilepsy Society has been active for 125 years and continues to fundraise to provide life-changing services to those with the disorder.

How many of us order death certificates to enhance our family research? I suspect that more birth and marriage certificates are purchased in England and Wales because of the details they provide about another generation in our family tree. But information about deaths can really improve our understanding of family life.

I was aware from the death index that my great great grandfather James Armstrong, died at the young age of 48. There was even a family story that he had sat down for breakfast and died in the chair. While it was interesting to be told this information I had no idea whether it was actually true. I ordered his death certificate which helpfully told me that he had died as a result of ‘The visitation of God’ on 9 March 1875. This seemed to cover a multitude of possibilities.

What was actually far more useful and extremely interesting was the Coroner’s Inquest, held as a result of his sudden death. Laid out before me were details of not only the day of his death but also his health up until a fortnight before. The family story that he had died in his chair at breakfast was true. James had felt unwell for two weeks before he died and was taking prepared charcoal to relieve his apparent indigestion pains. On the morning of his demise the charcoal was not effective so he asked his niece to light his pipe for him as he believed this would relieve his chest pains. His niece Ellen heard him fall to the ground within minutes of leaving him, and, after a brief struggle he died.

Details of the inquest were also reported in the local press which provided yet more information about his wife and seven young children. So it’s useful to bear in mind that information about deaths can be just as useful as births and marriages for improving your knowledge about your ancestors and also for confirming whether family stories have been passed down accurately.

I have spent the last few years researching the rich archive of case notes for patients admitted to asylums in nineteenth century Britain and Ireland. Many people have commented that they cannot imagine why I would be so interested in such a grim topic – am I mad myself? Perhaps I am – but the research has led me to co-write a book on the subject entitled ‘Lunatics, Imbeciles and Idiots: A History of Insanity in Nineteenth Century Britain and Ireland’, which I hope people will enjoy.

As a genealogist, I am naturally interested in any source of information that provides details about the identity and lives of others in the past. And, asylum case notes are a particularly rich source of ancestral information including photographs, hereditary illness within family and importantly first person accounts of how mental health disorders affected their lives and wellbeing.

The majority of genealogical sources provide a snapshot of a family on a specific day whether that be a baptism, marriage, burial or a census return. Medical case notes however, allow us to follow the lives of individuals on a daily or weekly basis for as long as they remained within the asylum. A good example of this is the case of Esther Eliza Taylor who was admitted to Parkside Asylum in Macclesfield, Cheshire in 1887. Her case notes reveal that Esther was wilful, stubborn and abusive towards her mother who was clearly at the end of her tether. However, as well as providing details of Esther’s mental health problems, the case notes also give details of her father who is described as ‘an inveterate drunk who had convulsions as a child’. Similar convulsions affected all of his children.

Hundreds of thousands of individuals were admitted to lunatic asylums in the nineteenth century. Many were discharged deemed to be recovered, but others remained there for life. Due to social stigma, episodes of insanity within a family are quickly ‘forgotten’ or brushed under the carpet. Subsequent generations may have no idea that their ancestor was once admitted to an asylum. But, for those of us with an inquiring mind, and let’s face it, most genealogists would describe themselves as nosy, these records are available for research.

The quickest way to determine if you had a ‘lunatic’ ancestor is to check the UK, Lunacy Patients Admission Registers, 1846-1912 on Ancestry. The patient case notes are held at county archives, but some collections have been digitised and are available to view online. Cheshire Archives and Local Studies have made their collection of Parkside Asylum case notes freely available using this method.

In order to highlight what a rich source of information these records are, my co-author Dr John Burt and myself will be giving a joint presentation at Who Do You Think You Are Live at the NEC in Birmingham on 7 April 2017.

+ Contact Information

Kathryn Burtinshaw M.Sc., Q.G

Pinpoint Ancestry

9 Spring Gardens,

Rhosddu,

Wrexham,

LL11 2NX

United Kingdom

Tel: 07576115513

+ Contact Information

Kathryn Burtinshaw M.Sc., Q.G.

Pinpoint Ancestry

9 Spring Gardens,

Rhosddu,

Wrexham,

LL11 2NX

United Kingdom

Copyright (c) 2023 Pinpoint Ancestry. All rights reserved.